A lot of discussions about Pete Rose took place last month as people were anticipating a lift of the lifetime ban the former big league legend succumbed to when it was discovered he had gambled in baseball games. For those fully aware of baseball history, that is the biggest sin a player/manager can commit. As a consolation, it was recently announced that Rose will be inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame.

Now, I’m not here to make a case for Pete Rose to be reinstated or for the ban to be upheld. I really do not care or do not know much about Pete Rose the person to care one way or another. I am indifferent in this matter. All I know is in the history of baseball, a player gambling is frowned upon and the penalties are usually severe. I’m still waiting for “Shoeless” Joe Jackson to be vindicated, but it doesn’t appear we will ever see that happening. To reiterate, Major League Baseball doesn’t like players gambling in their sport.

Instead, we will take another look at Pete Rose’s career, through the numbers. So the following is an ode of sorts to “Charlie Hustle” and how his career numbers compared to his peers.

Pete Rose played in the majors from 1963-1986. So we take a look back between 1960 through 1990 to see where Rose ranks in that particular 30-year span. All stats are courtesy of fangraphs.com.

COUNTING STATS (1960-1990)

Of course, playing for that long of a time span means you have a lot of opportunities to rack up the counting stats and Rose took full advantage. He played in the most games, had the most plate appearances, scored the most runs, and of course, had the most hits (to this day, Rose still owns the career record in hits) in this 30-year period. Carl “Yaz” Yastrzemski would finish second in these categories during the 30-year span being studied.

Rose has such a stranglehold on the hits’ record (4,256), he leads Yaz by about 800 hits, Rod Carew and Lou Brock by about 1,200 hits.

|

Player |

Hits | %Singles | %Doubles | %Triples | %HomeRuns |

|

Pete Rose |

4256 | 75.54% | 17.53% | 3.17% | 3.76% |

| Carl Yastrzemski | 3419 | 66.16% | 18.89% | 1.73% |

13.22% |

| Rod Carew | 3053 | 78.74% | 14.58% | 3.67% |

3.01% |

| Lou Brock | 3023 | 74.33% | 16.08% | 4.66% |

4.93% |

A grand majority of Rose’s hits came in the form of singles. A look at his distribution of hits and one can see that about 75 percent of his base-hits were of the one-base variety. That figure is pretty on par with other peers like Carew and Brock.

Rose also hit 746 doubles during his playing career. In the same 30-year span, The Yaz trailed Rose by 100 doubles (646), while the Kansas City Royals’ George Brett trails by 187 doubles. It is safe to say that what Rose lacked in home run power, he made up for it by hitting the ball into the gaps.

Charlie Hustle did not earn the nickname by pure coincidence. As far as triples go, Rose was third behind speedburners Brock and Willie Davis.

In terms of walks and strikeouts, Rose is fourth in walks (1566) and 12th in intentional walks, ahead of guys like Reggie Jackson and Harmon Killebrew.

Finally, in terms of batting average, of the 1,100 players that qualified for this study, Rose ranked tied for 20th overall in the traditional stat of batting average (.303) with Al Oliver.

In sum, Rose played in a lot of games and had a lot of plate appearances, but to his credit, he took full advantage of his opportunities to pad his stats.

WAR (1960-1990)

WAR, what is it good for? Well, for starters, WAR is short for Wins Above Replacement and it is a way to summarize a player’s total value into one convenient stat.

WAR is a good way to compare players, across time periods. Although it’s not perfect, it is one of the more useful stats in sabermetrics, especially when dealing with this type of exercise.

One of the aspects of the game measured by WAR is base running. In this instance, the stat mostly used during this 30-year time period was Weighted Stolen Base Runs (wSB), which measures a player’s value to his team by stealing bases. Rose had a career stolen base rate of 57 percent. His career wSB of -13.7 was tied for the 6th worst during this time period.

It turns out Charlie Hustle was better off just getting on base and wait for the next batter to drive him in. To be fair to Rose, other stats that measure base running efficiency were not calculated in Rose’s base running metric. So we may never know how valuable Rose’s base running ability was when he played. However, we do know that he was known as Charlie Hustle because of his aggressiveness on the base paths.

As far as Offensive WAR goes, we know Rose led all players in a lot of counting stats. So it’s not a surprise that Rose, despite the lack of power, ranks in the top 20 in O-WAR (354.7), finishing ahead of sluggers like Norm Cash, Dwight Evans, and Frank Howard.

Defensively, however, despite seemingly being versatile enough to play in multiple positions, Rose’s Defensive WAR ranks as the 24th worst in the 30-year span of this study (-143.0).

Despite his shortcomings on defense and base running, plus the lack of power, Rose’s offense is still good enough to earn a WAR of 80.2 during his playing career. The mark is good enough to finish eighth overall during the time span in question, finishing ahead of defensive wizard Brooks Robinson, teammate Johnny Bench, legendary base thief Rickey Henderson, annual autumnal hero Reggie Jackson, the great humanitarian Roberto Clemente, fellow singles’ hitter Rod Carew, and Cubs’ bigger-than-life personality Ron Santo.

OTHER ADVANCED STATS (1960-1990)

Back in those days, walking more than striking out was not a novelty. Rather it was an expectation. Needless to say, the game has changed drastically since Rose was at the peak of his game. But there’s no denying, no matter the era, Rose’s approach at the plate was great.

Despite the lack of in-depth plate discipline and Pitchf/x data for this time period, it’s plain to see that Rose had amazing approach at the plate. He was a tad on the aggressive side, but his Contact Rate must have been ridiculously high.

What we do have available is Clutch Rating, which is fangraphs.com’s way of measuring performance during high leverage situations. Usually, these clutch ratings favor the high contact/low power hitters who can adjust their approach to whatever the situation calls upon. They’ll choke up on the bat, not swinging for the fences, and looking to make good contact.

Since 2010, Kansas City Royals’ Eric Hosmer has led the league in fangraphs’ Clutch Rating (5.49). In the seminal baseball book Baseball Between the Numbers: Why Everything You Know About the Game is Wrong by the Baseball Prospectus Team of Experts, their system to measure “clutchiness” showed that former Chicago Cubs’ player Mark Grace was the most clutch player from 1972-2005. In fangraphs’ Clutch Rating, Grace ranks third (6.62) when compared to his peers that played with and against him, from 1988 until 2003.

No surprise that all three–Rose, Hosmer, and Grace—are known for being first basemen who lacked power, but had good approaches at the plate, and are known for their “clutchiness.”

By the way, Rose’s Clutch Rating is 9.07 per fangraphs; the highest from 1960-1990. Also worth noting that Clutch Rating is a counting stat, so the longer he played, the more plate appearances he garnered, and the increase in likelihood he would be placed in these high leverage situations.

So there’s no denying his approach, but his other advance metrics spotlight Rose’s lack of power. His Weighted On-Base Average (wOBA—basically, all hits are not created equal) of .354 (Adrian Gonzalez finished with that mark in 2015. Eric Hosmer’s wOBA was .355) is good. Unfortunately, when being compared to 1,100 hitters, Rose’s all-time wOBA ranked 130th overall (tied with eight others). So he finished better than 88 percent of his peers during the 30-year time span, but he’s jumbled up with players like Kevin Seitzer, Rusty Staub, and Glenn Davis. Very good players, but no one is making a push for their Hall of Fame inductions.

His Weighted Runs Created Plus (wRC+–a rate statistic that measures a hitter’s value, like wOBA, by using linear weights for each hitting outcome. Unlike wOBA, wRC+ adjusts for league and park effects. League average is 100. Any number above 100 is above average. Any figure below 100 is below average) of 121 ties him for 117th place with the likes of Jeff Burroughs, Leon Durham, and Bill Madlock. His 2015 wRC+ comparison is Jason Heyward.

So based on the advanced stats, Pete Rose’s support to be in the Hall of Fame are strictly based on his counting stats, which is a testament to his endurance and longevity in the league. But what if Rose didn’t have the all-time hits’ lead? What if he didn’t play in 24 seasons?

HALF A ROSE

Rose played in 24 seasons in MLB. So the question I have now is what would Pete Rose’s counting stats look like if he only played in 12 seasons? Basically, cut his career counting stats in half. Not the most scientific of methods, but it offers us a different perspective on Rose’s career:

|

Pete Rose |

Hits | Runs | Singles | Doubles | Triples |

Home Runs |

|

24 Seasons |

4256 | 2165 | 3215 | 746 | 135 | 135 |

| 12 Seasons | 2128 | 1083 | 1608 | 373 | 68 |

68 |

Suddenly, his numbers aren’t as impressive. They’re good, but it’s not something that will create an outcry to have him get inducted into the Hall outside of Cincinnati.

Rose’s 12-year career stats are very similar to Luis Aparicio, Bert Campaneris, and Dave Concepcion. Great players in their own right, but all three of those players do not carry the reverence that Pete Rose receives whenever his name gets mentioned.

2010-2015 PETE ROSE

The next question here is, “who is the modern day Pete Rose?” And do those types of players with similar skill sets have a chance to ever make it into the Hall of Fame?

To see who Pete Rose would be comparable to in today’s game, we have to look for position players who first and foremost, have a similar approach to Rose. The key word is “similar” as not too many players have that same exact skill-set. Secondly, we’re in an era where players are simply striking out a lot more than walking. That’s just the way it is.

So to help in our search, we sort players by the best Walk:Strikeout ratios. The next step is to see which of these players have similar production value as Pete Rose had. Here are the results:

|

Pete Rose 2010-2015 Comps |

||||

| Player | OPS | wRC+ | wOBA |

BABIP |

|

Pete Rose |

0.784 | 121 | 0.354 | 0.319 |

| Ben Zobrist | 0.780 | 120 | 0.343 |

0.296 |

|

Joe Mauer |

0.802 | 120 | 0.350 | 0.344 |

| Dustin Pedroia | 0.799 | 117 | 0.350 |

0.312 |

Ben Zobrist, Joe Mauer, and Dustin Pedroia are not only the best the modern game has to offer in terms of plate approach, but all three have some of Rose’s characteristics as a player:

- Zobrist has his versatility,

- Mauer’s production at first base represents Rose’s time as the primary first baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies,

- Pedroia’s fire and feistiness are comparable to Rose’s “Hustle.”

Most importantly, they all have similar stats’ lines and are the closest baseball has seen to duplicating Pete Rose’s skills and abilities. If Pete Rose did not have the opportunity to play 24 seasons and accumulate high counting stats, a combination of these three players is what Pete Rose would look like in today’s game.

Now, do any of those three players deserve a spot in the Hall of Fame? Well, Pedroia is 32 and would need to play 10 more seasons to have a shot at 3,000 hits, but his style of play appears to have finally caught up to him. Joe Mauer, turning 33 in April, if he plays 9-10 more seasons, has a shot at 3,000 hits, but Mauer’s skills are already deteriorating rapidly. Ben Zobrist, to be 35 in May, if he were to play for as long as Pete Rose did when he retired from playing (age 45), Zobrist might be able to flirt with 3,000 hits, but that would be asking a lot out of Zobrist.

How Rose was able to play for such a long time and be so productive when it came to the counting stats that all, but locked him into the Hall of Fame is a discussion for another day.

CONCLUSION

So who is Pete Rose? He is a player who played for 24 seasons and racked up the counting stats over the span of his career. A closer look, however, shows a player with incredible approach at the plate, but lacked power as he often would settle for singles and the occasional double. Or as many “old-school” baseball fans would say, “he opted for the right baseball play.” To his credit, this approach resulted in him being rated as one of the most clutch players from 1960-1990.

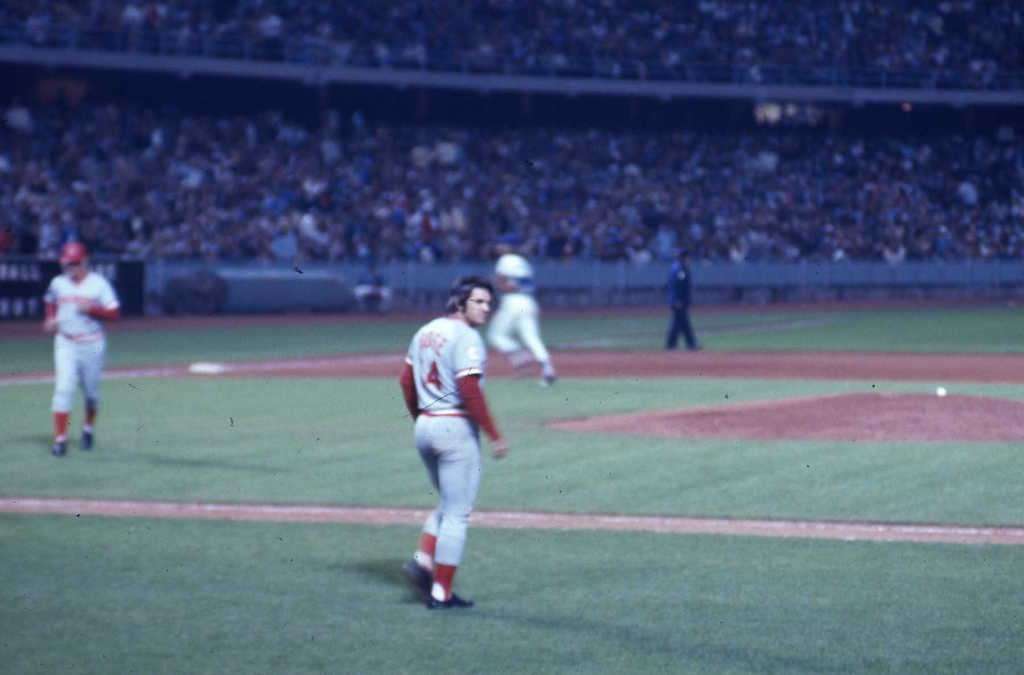

Feature Image Credit: by jvh33 of Flickr, from a 35mm slide. http://www.flickr.com/photos/jvh33/739372113/in/set-72157600121019053/ C.C 2.0